Tags

American chicken, Back to work, Bus, diablé, Flan aux lardons, Hygiene, Justice system, Picture, Poulet à l’americaine, Quiche Lorraine, Stock

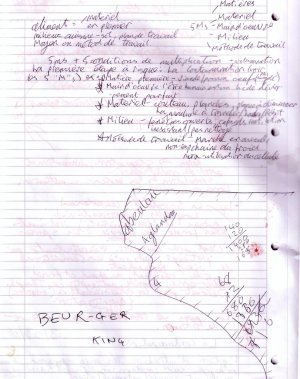

Delphine drives me to school this morning. I’m still not up to cycling, so she drops me off on her way to work and I’ll get the bus home this evening.I apologise to Chef for missing last week and he checks to make sure I’ve been given the recipes they worked on while I was away. I’ve already copied them from Mr Whippy – Pascal, the guy who shares my workstation and who can whip anything into a better froth than I can. Including, obviously, the genoise they made last week. Chef moves on. I can’t tell if he’s mad at me for not coming last week or disinterested – he doesn’t seem impressed at my tales of the doctor wanting to cart me off to hospital. Clearly, unless you’ve lost entire limbs, preferably more than one at once, you should come to work. Not being able to work out which way is ‘up’ is no excuse at all.So today we’re doing ‘Poulet à l’americaine’ and, like so many things given foreign names by the French, it bears little resemblance to anything Americans might do to a chicken. Well, that’s not true – essentially American-style chicken in this case means quartered and grilled with a tomato sauce, but Americans aren’t the only ones to treat poultry thusly. Mind you, Americans get away lightly – just about the only foods the French have named after the English are ‘légumes a l’anglais’, vegetables boiled in salted water, and crème anglaise which is really nothing like custard at all (no powdered eggs, for example). Everything else à l’anglaise is really quite rude – try checking out ‘J’ai les anglais qui arrivent’ or ‘Filer à l’anglais’ if you have a strong stomach. NSFW.American chicken starts, as do all good French recipes, with some good stock; chicken, in this case, or ‘fond brun de poulet’, chicken stock made with roasted bones. At the restaurant we make our own but, since we don’t have enough time at school today, we use the powdered stuff. Add in a little tomato concentrate, carrots and onion and we’re good to go.Well, good to start going. You take this sauce, reduce it down and then ‘diablé’ it, devil it by adding chopped shallots, white wine, white wine vinegar and ‘poivre mignonette’ which, literally translated, means ‘cute little pepper’ but in practise means cracked black pepper. ‘Diablé’ because anything vaguely hot in French gets a wicked name – the French simply cannot cope with hot, spicy food and need to give it a name that says ‘Warning! Warning! Danger of Death!’Wimps.So then we actually get down to grilling the chicken, first scrubbing the hot grills (cast iron plates that sit over a couple of gas burners) and then, well, grilling the chicken on them after seasoning and oiling the meat. This makes pleasingly large flames to frighten the girls, which is always fun.We grill a few tomatoes and mushrooms too, and finish the whole lot off in the oven. Which sounds like a simple idea but is something that had simply never occurred to me to do before I started cooking professionally. Grilling things on hot pans gives them a nicely coloured exterior (Maillard reactions! Look it up!) but then goes on to burn the meat if you leave them on the hot gas. You can turn down the gas and keep turning the meat repeatedly, but it’s simpler to whack the whole thing into the oven and let it finish off there at a lower temperature, cooking the inside through without burning the outside. Good tip there, food lovers, which only seems obvious once you know about it.Midday today and I eat a quick lunch to give me time to copy up notes from last week’s classes – the people involved in the justice system (judges, lawyers, bailiffs and so on), plus ‘La fiche de stock’, stock sheets which is how you’re supposed to keep track of what’s in the pantry by checking stuff in and out. I’ve never worked in a big enough kitchen to warrant using such a thing – they’re all small enough to stand in the pantry or cold room and say, ‘Hmm, I see that we need more flour and aubergines.’ Much less complicated than the enormous sheets Chef has handed out where you need a minor degree in accounting just to work out how much olive oil you have and whether you should order some more. Yet another thing that, if you need to have it, would be easier to do on a computer but all the French restaurants I’ve seen bar one have used exactly no computers at all. And that one used wireless handsets to take orders which were then printed out and passed around the kitchen.Then on into a Hygiene class where we learn more about bacteria, including the fact that it takes just two hours for them to multiply in whatever food you leave lying around to reach critical mass, the point where they gain sentience, rise up from your work surface and suffocate you in a glooping mass of grey goo. Well, I exaggerate slightly for effect but that’s the general idea. It seems obvious to me that some things will go off more quickly than that, while other things can be left out for a lot longer than two hours, but again for the purposes of passing this exam the limit is two hours. We also learn about ‘sporification’, whereby the spores of bacteria can survive even boiling and that the only way to kill them so they can’t hatch into new, killer baby bacteria and fill your life with grey goo is to sterilise them at temperatures over 140 degrees Centigrade.And then you can re-contaminate stuff by, say, letting beetles crawl over it when you leave it uncovered sitting on a windowsill. Good grief. All fine stuff but it doesn’t take an hour for a grown adult to understand it. This picture shows what I do for the next 50 minutes after I’ve grasped the meaning of this week’s lesson (which, don’t forget, is being given in French so I have to translate it first before I can understand it. The text at the top is my notes on bacteria. ‘Aglandau’ and ‘abeulau’ refer to two different types of olives from which olive oil is made – David and I were having a discussion about the merits of each instead of paying attention to teacher. ‘Beur-ger King’ is the name of a new, Arabic chain of burger bars recently launched in Paris, ‘Beur’ being an Arab word. The sums are me working out my wages and tax owed thereupon. The drawing bit is me doodling.).I love the practical cooking parts of this course, and the classes on cooking techniques. And while I understand the necessity of teaching hygiene, nutrition and legal stuff to future restaurant chefs I do think it could be done more by way of handing out a small pamphlet at the end of the year, rather than making a group of grown-ups with better things to do than sit in a hot room and have a nap.We do Quiche Lorraine this afternoon. The quiche is fine, any fule can fill a pastry case with flan, vegetables and bits of bacon. Bacon, of course, is counted as a vegetable in France so Quiche Lorraine is a vegetarian dish over here. I jest not; I’ve since worked for a couple of weeks in a restaurant where the ‘vegetable of the day’ was regularly ‘flan aux lardons’, flan with bacon bits in it. When I explain that, of all the ingredients – milk, eggs, bacon – none come from the food group known to the rest of the world as ‘vegetables’, I’m told ‘There’s salt in it!’. Well, salt isn’t a vegetable either. But flans are, apparently, so Shut Up.Back home on the bus. Bus routes are the same all over the world – this is my first trip on a bus in Avignon and its route planners have followed the rules used by bus route planners everywhere: check departure point, check arrival point, draw straight line between two, then visit every other place you can think of within three kilometres of that line so the journey takes an hour instead of 10 minutes. And above all when you’re within 500 metres of the arrival point make sure you take an extra detour so as to frustrate passengers to the maximum.And then back to bed. Standing up all day from 8 am to 6 pm has done me in.

This picture shows what I do for the next 50 minutes after I’ve grasped the meaning of this week’s lesson (which, don’t forget, is being given in French so I have to translate it first before I can understand it. The text at the top is my notes on bacteria. ‘Aglandau’ and ‘abeulau’ refer to two different types of olives from which olive oil is made – David and I were having a discussion about the merits of each instead of paying attention to teacher. ‘Beur-ger King’ is the name of a new, Arabic chain of burger bars recently launched in Paris, ‘Beur’ being an Arab word. The sums are me working out my wages and tax owed thereupon. The drawing bit is me doodling.).I love the practical cooking parts of this course, and the classes on cooking techniques. And while I understand the necessity of teaching hygiene, nutrition and legal stuff to future restaurant chefs I do think it could be done more by way of handing out a small pamphlet at the end of the year, rather than making a group of grown-ups with better things to do than sit in a hot room and have a nap.We do Quiche Lorraine this afternoon. The quiche is fine, any fule can fill a pastry case with flan, vegetables and bits of bacon. Bacon, of course, is counted as a vegetable in France so Quiche Lorraine is a vegetarian dish over here. I jest not; I’ve since worked for a couple of weeks in a restaurant where the ‘vegetable of the day’ was regularly ‘flan aux lardons’, flan with bacon bits in it. When I explain that, of all the ingredients – milk, eggs, bacon – none come from the food group known to the rest of the world as ‘vegetables’, I’m told ‘There’s salt in it!’. Well, salt isn’t a vegetable either. But flans are, apparently, so Shut Up.Back home on the bus. Bus routes are the same all over the world – this is my first trip on a bus in Avignon and its route planners have followed the rules used by bus route planners everywhere: check departure point, check arrival point, draw straight line between two, then visit every other place you can think of within three kilometres of that line so the journey takes an hour instead of 10 minutes. And above all when you’re within 500 metres of the arrival point make sure you take an extra detour so as to frustrate passengers to the maximum.And then back to bed. Standing up all day from 8 am to 6 pm has done me in.